What Happened to Gang Peace?

By Richard B. Muhammad and Charlene Muhammad Final Call Staffers | Last updated: May 17, 2012 - 9:09:26 AM

Los Angeles Bloods and Crips agree to a truce in 1993. Photo: AP Wide World Photos

|

Activists share lessons from movement to quell urban violence

(This is the first in a series of articles about the gang peace movement that started in Los Angeles in 1992 and spread across the country. It examines the roots of the movement, things to be learned, shares the stories of peacemakers and looks at current challenges to ending violence and building a movement for social and economic justice.)

LOS ANGELES (FinalCall.com) - It's been 20 years since the historic gang truce between the Crips and Bloods in Los Angeles sparked peace work and inspired a national movement to quell urban violence in America's streets and save lives.

Participants in the 1993 Gang Summit. Photo: Coalition for A Better Life

|

Gang members from four major housing projects in the Watts section of Los Angeles, Imperial Courts, Jordan Downs, Nickerson Gardens and Hacienda Village, established a peace treaty on April 28, 1992 but had been working on ways to bring about peace since the 1980s, say anti-violence activists.

“One of the primary reasons there was a need to come together because 1987-88 was the height of the gang war in L.A. We were experiencing about 1,000 to 1,100 murders a year and nobody was really winning the war that we were waging against each other,” explained Aqeela Sherrills, director of Resources for Human Development California, a gang intervention organization.

The activist, a former Crips gang member from Jordan Downs, spearheaded the 20th Anniversary Reunion Celebration of the Los Angeles “Peace Treaty” in Watts late last month.

According to Mr. Sherrills, people rallied for peace after LAPD offi cers killed unarmed resident Henry Peco at the Imperial Courts Housing Projects without provocation. Mr. Peco’s nephew, Dwayne Holmes, and others organized a committee for justice and talks between a few people from the various housing projects increased.

Parents of some gang members had also been Muslims prior to 1975 but with the departure of the Hon. Elijah Muhammad, their children were involved in street life. However, their affi nity for the Muslim movement was not destroyed. “Being that we all grew up in the Nation of Islam, we were tied into Minister Farrakhan and the Stop the Killing Movement that was happening all across the country,” Mr. Sherrills said.

“One of the primary reasons there was a need to come together because 1987-88 was the height of the gang war in L.A. We were experiencing about 1,000 to 1,100 murders a year and nobody was really winning the war that we were waging against each other,” explained Aqeela Sherrills, director of Resources for Human Development California, a gang intervention organization.

The activist, a former Crips gang member from Jordan Downs, spearheaded the 20th Anniversary Reunion Celebration of the Los Angeles “Peace Treaty” in Watts late last month.

According to Mr. Sherrills, people rallied for peace after LAPD offi cers killed unarmed resident Henry Peco at the Imperial Courts Housing Projects without provocation. Mr. Peco’s nephew, Dwayne Holmes, and others organized a committee for justice and talks between a few people from the various housing projects increased.

Parents of some gang members had also been Muslims prior to 1975 but with the departure of the Hon. Elijah Muhammad, their children were involved in street life. However, their affi nity for the Muslim movement was not destroyed. “Being that we all grew up in the Nation of Islam, we were tied into Minister Farrakhan and the Stop the Killing Movement that was happening all across the country,” Mr. Sherrills said.

Beginning in 1980s, Min. Farrakhan spent some 10 years doing a series of Stop the Killing lectures, appealing to youth to stop fratricidal violence, warning of government and law enforcement fear and deadly government crackdowns that the violence would justify. The nascent neighborhood peace activists sent about 25 young men to hear Min. Farrakhan’s 1989 message at the L.A. Sports Arena. They were invited to attend peace talks at NFL Hall of Famer/actor Jim Brown’s home and about four or five subsequent meetings.

Fred Williams of Los Angeles, second from left, addresses reporters in Washington Feb. 4, 1993 to discuss a national gang truce timed to the first anniversary of the Los Angeles riots. Joining Moss, from left are, Spike Moss of Minneapolis; Williams; Rev. Dr. Benjamin Chavis Jr. of Cleveland; and Carl Upchurch of central Ohio. Photo: AP Wide World Photos/Doug Mills | (R) Minister Farrakhan meets with members of street organizations at the National House in 1993.

|

No agreement was reached, but key relationships formed between neighborhoods and with Mr. Brown, according to Mr. Sherrills.

Out of that, he and Mr. Brown co-founded the Amer-I-Can gang intervention organization, which grew to 15 chapters. The organization thrived by teaching a life skills curriculum to gang members who wanted out of the life. It became part of the basis for the peace treaty, Mr. Sherrills said.

The activists organized the peace treaty a day before the Rodney King verdicts were read. The acquittals of the police officers and the subsequent rebellion not only resulted in fires destroying parts of the city; it also fueled efforts to find unity in the face of police violence and a common enemy. Some say, it also struck fear in the hearts of a ruling elite seeing fearless young men, boiling civil unrest and anger over racial oppression.

“It changed the quality of life in our neighborhood,” recalled Mr. Sherrills. “The first two years of the gang truce, gang homicides dropped 44 percent, dismantling the C.R.A.S.H. Unit in the neighborhood. And as a direct result of our work today, L.A. is experiencing a 40-year low as relates to gang violence and homicide,” he told The Final Call.

Delegates to the 1993 Kansas City gang Summit, including the late Omar Ali-Bey (center front), co-founder of the Coalition for A Better Life and Peace in the Hood. Photo: Coalition for A Better Life

|

But police and politicians have consistently taken credit for the peacemakers’ work, which was a community-driven strategy, Mr. Sherrill continued. God blessed the process, he said.

Through Amer-I-Can, he traveled to about five cities, including Cleveland, Portland and Chicago. He lived outside of Los Angeles for approximately four years and helped to organize peace agreements.

The 20th year celebration acknowledged numerous men and women consistently engaged in peace keeping efforts across the country. While levels of death and violence are lower than at the height of gang wars often connected to the crack cocaine epidemic, feuds and fight over drug turf as good signs, activists admit challenges exist: Discipline and control within street organizations is no longer as strong as it once was; it is harder for a few individuals control large groups. Conflicts within groups can result in battles once reserved for outsiders. The lack of resources or a “peace dividend” remains a problem. There is a kind of generational disconnect; too few younger members were groomed to take leadership roles; many don’t know the lessons of the past. The economy is worse now than in the early 1990s when the urban peace movement took flight.

On the upside, they say, are years of lessons learned and influence still wielded inside street groups, even if things may be challenging. Lastly, they say, lives are still being changed because of commitments to go after youth.

What has happened to gang peace?

When Los Angeles gang members announced peace efforts there was little applause and plenty of skepticism, but some significant events lent support to peacemaking. Min. Farrakhan, who had always reached out to youth and urged so-called gang members to stop violence, brought the Nation of Islam’s Saviours’ Day convention to Los Angeles in October 1993 as a tribute to the peace treaty between the Crips and the Bloods.

Minister Farrakhan stands with mothers who lost children to street violence in 2004.

|

“My real reason for being here is to personally pay tribute and honor to Almighty God for putting his spirit in the Bloods and Crips who have initiated a truce by the power of God himself,” said Min. Farrakhan in his Saviours’ Day address that year.

Before Saviours’ Day 1993, there had been major national gang summits in late April and early May in Kansas City; then in Cleveland in June, followed by St. Paul, Minnesota in July and Chicago in October. Min. Farrakhan was an early supporter of the summits organized by what became the National Urban Peace and Justice Summit, under its late leader Carl Upchurch, who turned his life around after serving prison time. Prince Asiel Ben Israel of the Hebrew Israelite community, Earl King of No Dope Express and former street leader Wallace “Gator” Bradley were among those who led the early efforts in Chicago. Then there was activist Spike Moss and Vice Lord leaders out of the St. Paul-Minneapolis area.

Peacemakers started working together and Latino street organization leaders and members attended the first urban peace summit. Longtime activist Cesar Chavez had died shortly before the Kansas City gathering and the meeting was dedicated in his honor, recalled Khallid Samad, a longtime activist and Muslim leader based in Cleveland. Mr. Samad, with the late community leader Omar Ali-Bey, was part of the group that worked on early summits.

Min. Farrakhan spoke July 17 during the summit in St. Paul, urging the youth to find ways to make peace and pointing out the failures of the elders and families to give young people the nurturing and love they need. The young men and women find camaraderie with one another in street organizations, he noted. But, the Minister, urged the young people to give up violence and to accept responsibility for themselves and their community. “These are wonderful young people. They just need a chance and right guidance. That’s the premium today: Right guidance,” he said.

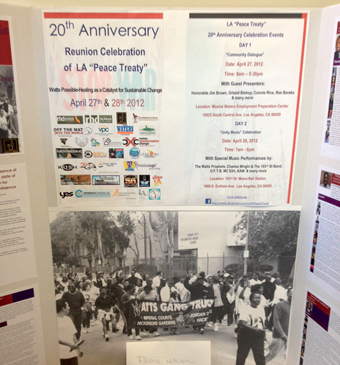

1993 Gang Summit march in Kansas City, Mo.

|

“Brothers and sisters if we don’t stop killing one another, God is going to give you your own blood to drink because he has a killer that has been killing since he has been on the planet,” Min. Farrakhan warned from the pulpit of Mount Olivet Missionary Baptist Church in St. Paul, Minn.

Khalid Raheem, president and CEO of the National Council for Urban Peace and Justice, was at the summit in Kansas City in 1993.

The movement is still vibrant, still relevant, because violence exists across the country and the social conditions—poverty, oppression, racial discrimination, police brutality—that created gangs still exist, Mr. Raheem said.

The urban peace and justice movement will be needed until “institutional changes are made that that are beneficial to poor, Black and Brown people,” Mr. Raheem added.

With the L.A. rebellion and peace came fear from the ruling powers, which saw a potential threat and sprinkled a few dimes and dollars to blunt that perceived threat, he continued. Those who were trying to stem violence took the money, not selfishly but pursuing the traditional non-profit model and using the money to help fund community work, he said. Nonprofits, however, will never do revolutionary work, said Mr. Raheem. They can be helpful but face legal and financial constraints, he noted.

Lessons learned over 20 years

Urban peace needed proper infrastructure to push forward nationally and peacemakers meant well and had some skills, but skills needed for movement and organization building were lacking, said Mr. Raheem, sharing his honest critique of two decades of work.

| In 1993, Hip Hop Artist Kam released the hit single "Peace Treaty" to celebrate the peace treaty following the LA Rebellion. |

It can also be hard to take an unpopular position with nonprofit status, which can compromise the integrity of the movement and create divisions among leaders and peace workers, Mr. Raheem pointed out. The movement must to be supported by the people who are being fought for, he said. The goal must also be justice, “if you can’t bring about justice you can’t have any peace,” Mr. Raheem said.

He also feels there was a failure to take a firm position against drug dealing and drug trafficking. There were compromises in trying to bring more people into the peace process and urging people to go legit with tainted money, but it hurt movement credibility, he said.

Then like other movements, much of the urban peace movement was tied to personality instead of platform and principles, Mr. Raheem continued. If you follow a personality, it can be hard to challenge the person for not doing the right thing or deal with conflicts between conduct and organizational principles and platforms, Mr. Raheem noted.

Today street organizations are more fragmented as leaders were removed by police or government, or stayed engaged in negative behavior that allowed for them to be targeted, he said. Lacking leadership, unity deteriorates and individualism fills the void, he said.

But, Mr. Raheem continued, activists work together inside and outside their respective cities and states, whether confronting youth gang and drug related violence, running afterschool programs, serving at-risk students, offering substance abuse counseling, helping the children of incarcerated parents or dealing with other fallout from drugs and violence.

Dr. Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr., executive director of the NAACP stands among participants of the National Urban Peace and Justice Summit on Friday, April 30, 1993 in Kansas City, Mo. They are listening to Kansas City Mayor Emanuel Cleaver welcome them during the opening breakfast session. Photo: AP Wide World Photos/Cliff Schiappa

|

There is public policy work, such as a national campaign for drug decriminalization, and call for an amnesty program for small level drug use and drug selling, he said. Drug convictions today can mean loss of voting rights and ineligibility for everything from federal assistance for college to subsidized housing, not to mention trouble finding a job.

Fundamentally the battle is against White Supremacy which holds Blacks and Browns down and uses poor Whites, said Mr. Raheem. The battle is also to destroy Black self-hatred and Black group hatred, he added.

Khallid Samad, of Cleveland-based Coalition for a Better Life, recalls the 1980s and efforts of Muslims to fight the drug epidemic and redirect youth. He points to the work of Omar Ali-Bey in Cleveland, Imam Jamil Al-Amin, formerly H. Rap Brown in Atlanta, Imam Siraj Wahaj in New York as well as Nation of Islam anti-drug patrols in Washington, D.C., and Muslims in other cities.

Drug dealing which brought the violence was manipulated by outside forces, said Mr. Samad, pointing to the 1980s arms for drugs Contra scandal and the legacy of Freeway Ricky Ross, who helped spread crack cocaine along the West Coast and other parts of the country. Journalist Gary Webb documented ties between Freeway Rick and a Contra leader in 1996. His newspaper later backed away and retracted the “Dark Alliance” series. Mr. Webb, who later committed suicide, insisted his reporting was true.

Mr. Samad believes those early efforts, which also included Muslims in Los Angeles who were trying to combat drugs and violence, helped till soil for seeds that later bloomed as peace work.

The night before the peace treaty was signed, street organization leaders met at a mosque in Los Angeles and seeing streets filled with cops for no reason as they left they realized their power to stop the madness, said Mr. Samad.

“As opposed to a peace dividend, we got a backhand, from government, police and the pundits who didn’t know what was going on,” he said, describing the response to peace efforts. Muslims were especially shunned, Mr. Samad said.

Though crime and violence fell in every major city, the prison population exploded, he said. So as young men out their guns down the Justice Dept. and other law enforcement agencies began to crackdown, he said. But, Mr. Samad, noted after the peace pact came the Black Leadership Summits and the 1995 Million Man March, with its impact on the 1996 national elections, thousands of adoptions and other positive work. Yet in 2012, “we still don’t have an urban policy in America,” he said.

Mr. Samad believes there must be continued efforts to build institutions that serve Black neighborhoods, which are now markets for White-run non-profits, Ritalin-pedaling mental health service providers and fee for service agencies.

Blacks need to more strongly challenge institutions that control philanthropic resources, and economic development, he added. His non-profit has never been fully funded by outsiders but serves youth with anti-gang work, after school, and summer and other programs.

Within a year of the L.A. truce a national meeting was held in Chicago and supported by Min. Farrakhan and included the Rev. Jesse Jackson, who described it as an urban policy meeting, and then-NAACP Executive Director Benjamin Chavis, who had called for NAACP outreach to gang members. Street organizations from 28 cities participated.

The gathering focused on stopping gang violence, combatting drugs and creating jobs, similar to call from the first summit. The national work was built on local efforts.

Early on people got together from different neighborhoods, hoping for remedies but at least stopping the shooting, said Minister Ben “Taco” Owens, of the Southern California Cease Fire Committee.

Display at Peace Treaty 20th anniversary gathering in Los Angeles.

|

“It was a celebratory moment because it was almost as if the war was over. Communities began to blend together at functions and events but unfortunately, sometimes alcohol and maybe even drugs entered. Those escalated to other series of violence to where we found at end of day, the same year that was proclaimed the peace treaty year was the most deadliest year in the history of L.A. County,” Min. Owens said.

As peace efforts grew there were not enough people of influence to make things happen or continue the process if someone was lost, through death, or other means, he said. “We had losses, like Rocky (Rolland Miller) and Bo (Bo Taylor of Unity One) and others who meant a lot for gang peace. There were not enough mentees to take up those positions to pick up where the brothers left off. As a result we couldn’t keep up with the pace,” he said.

What bothers Min. Owens is the movement had 20 years to get its act together and groom the younger generation. There was an opportunity to teach what 1992 was about, but we dropped the ball, he said.

“It should have been communicated so at some point we don’t have these 30-40-year-old wars. It’s amazing. You have generation after generation fighting wars, with hostility against different communities when most of them weren’t even born when the initial conflict started,” Min. Owens said.

Despite the challenges and some shortcomings, Min. Owens believes onetime gang members turned peacemakers are important, but everyone has a role to play. “L.A.’s averages are going down every year. There’s between 550-620 homicides a year and out of those, less than one-third of those homicides are gang related. So the rhetorical question is which came first, the violence or the gangs? No homicide is good, but if you have only one-third of them then who’s responsible for the other two-thirds?”

Gang violence can’t be looked at solely, when there are so many problems with violence in the Black community, Mr. Owens said. “For years we’ve told and taught children if somebody hits you hit them back but we never took time to tell our children the peace process, what is peace and ‘don’t hit your brother or sister,’” Mr. Owens said.

People also have to self-improve, according to Ansar Stan Muhammad, co-founder of the H.E.L.P.E.R. Foundation (formerly known as Venice 2000). He and co-founder Melvin Hayward were instrumental in launching the Southern California Cease Fire Movement.

Entrenched in drugs, guns and gangs in 1992, he was sent to prison. When he returned home in 1995 as a Muslim, he immersed himself in “Self-Improvement: The Basis for Community Development” study guides created by Min. Farrakhan.

“I and we (Mr. Hayward) felt before we could improve the quality of anybody’s community, we had to improve ourselves first,” he said. “It is a well kept story that the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan was the nucleus that ignited the movement in L.A. Because he was doing the Stop the Killing tours at the time, the atmosphere was right for individuals to come together. Prior to that no one was talking about stopping the killing, peace treaties or none of that. It wasn’t even a discussion,” Mr. Muhammad recalled.

He risked parole violation to attend the 1995 Million Man March and brought back photos. His parole officer was impressed and didn’t report him. “The greatest intervention work is the Nation of Islam. Brothers have transformed their lives through the teachings of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. We’ve gotta start saying it because that’s real talk, after seeing all we’ve gone through.”

There are also success stories, like the new life of Anthony Blockmon, which show gang intervention works, Mr. Muhammad continued.

Mr. Blockmon grew up in Venice, Calif., heavily into gang life with family and friends. His father was killed when he was nine. Angry, hurt and without a role model he was “jumped,” or beaten into a gang at age 11. He was in the fifth grade and captivated by older gang members.

Though his mother didn’t like it, he smoked weed, sold crack cocaine, glorified gang life and was jailed as he turned 18. He went in and out of jail at least six or seven times and went to prison twice, hating incarceration but fronting like it didn’t matter.

Once when he returned home, he reconnected with his childhood girlfriend. He went back to jail but started to pray, especially when while he was in jail, his girlfriend was incarcerated too. He has become the youngest board member of the organization that helped him.

Gang members, former gang members and activists commemorated peace in Hattiesburg, Miss., May 10-13 at the 10th anniversary of the Brothers in the Struggle gathering honoring founders of Chicago’s Gangster Disciples street organization.

The theme was “From the Womb to the Tomb, From Murder to Excellence,” according to Wallace “Gator” Bradley, a Chicago-based political consultant and activist. He is a onetime “G.D.” The event was designed to celebrate the women and delivered a consistent, pointed message from legendary Gangster Disciple leader Larry Hoover, who remains incarcerated. “Stop killing one another. Stop the raping of women and children. Stop the disrespect and robbing of our elders,” Mr. Bradley told The Final Call.

Mr. Hoover’s son, Larry Hoover, Jr., embodied the essence of his father’s message of transitioning from Gangster Disciple to Growth and Development. The senior Hoover, serving six life sentences for murder, created the Growth and Development ideology to help gang members turn their lives around by creating non-profits, providing jobs, giving back what they’ve taken from and helping to stabilize communities, said Mr. Bradley.

Attendees from 16 counties in Mississippi and 16 states traded guns and pistols for chess pieces and basketball games, Mr. Bradley told The Final Call. They resolved to go back home and build up their cities because for every victim there’s a family member locked behind bars. “Our message is stop the killing or be ostracized from the community,” Mr. Bradley said.

Rebuilding requires funding and resources, and money has impacted gang peace both good and bad, activists like Daude Sherrills, Aqeela’s brother, note.

“The counterintelligence movement came in after seeing our success and the decline in violent crime taking place in L.A. And I don’t know if that became a problem with certain agencies who utilized violence, high crime and gang wars as their fiscal fundraiser tactics, but something was tied to that,” Daude Sherrills said. He argued law enforcement and politicians never really supported or endorsed the gang peace movement and felt their coming together was a threat.

There were sting operations that landed brothers who truly wanted peace in jail, he said.

“There was a void and the transfer of communication and responsibility kind of fell on a younger generation that we allowed to be a part of the whole movement, but weren’t invited in to sit at table and take on this plight of uplifting the community and keeping violence to a low through peace and communication with other neighborhoods,” he said.

According to the activist, the peace plan has always been national, not just L.A.-focused, and had some basic goals. “When we created the peace treaty, there was a counter against that because it was a movement that came from the ground and the message was clear: We’re men. We want our tax dollars spent in this direction, in our communities, among Black businesses, and that’s counter to what they planned … It’s like a war you can’t win,” he said.

Related news:

Gang wars report proves racial targeting of Black males (FCN, 08-05-2007)

A Special Message to Street Organizations (Minister Farrakhan, 08-05-2007)

Amidst accusation of violence against police, gang truce continues (FCN, 08-22-2004)

Piecing the peace together (FCN, 06-10-2004)

Rival Newark gangs sign ceasefire (FCN, 06-01-2004)

No comments:

Post a Comment